The Olympics have come a long way since the earliest record of the ancient Greek Olympiad in 776 BC, when the only event was a simple foot race. Women, slaves and ‘impious persons’ were banned even from attending the games.

(While that all sounds a bit dour, proceedings were made slightly more exciting by the fact that all athletes competed in the nude.)

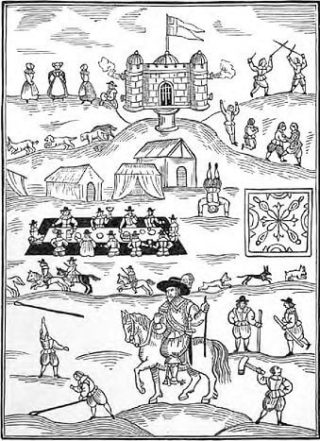

The first post-classical ‘Olimpick’ games took place in Chipping Campden in Gloucestershire in 1612, and it is a small relief that sporting tourists no longer have to descend on dozy market towns in the Cotswolds to get down to some good spectatin’.

The range of Olympic destinations has blossomed since the modern revival of 1896, going from Europe to North America to Australia to Japan, South Korean and China. Rio de Janeiro 2016, though, has the distinction of being the first-ever Olympic Games held in South America.

From a linguistic point of view, the South American continent is often thought to be synonymous with the Spanish-speaking world. It’s a strange misconception given how mind-numbingly enormous Brazil is in every way compared to all of its neighbours. By landmass, Brazil accounts for 47.3% of South America’s landmass, and shares borders with ten of the twelve other countries on the continent. And out of a total continental population of some 400 million, over 210 million South Americans are indeed Brazilian.

That makes it high time to give a quick tour of this underappreciated titan of the major world languages – with phrases ranging from the handy to the historical to the hopelessly untranslateable.

1) Beleza

/be-le-zuh/

Meaning: ‘Beauty’ – but also ‘hello’, ‘hi’, ‘how’s it going’,’ good’, ‘great’, ‘cool’, ‘thanks’, ‘see ya’ and pretty much any other kind of filler-word in the right context.

Learning foreign languages is a Sisyphean faff. Not only is it hard to get the ball rolling, but you also never fully arrive at the destination; there’s always something left to learn.

That means we should appreciate the rare occasions when a word of beautiful polyvalency rears its head, and sorts you out in countless situations.

‘Beleza’ is an effortlessly cool word which can start and end any conversation on a breezy note.

Beleza? ‘Is everything good?’

Beleza. ‘Everything’s great.’

Good to know, isn’t it? You’re welcome.

2) Fica tranquilo

/fee-kuh tran-kwiloo/

Meaning: ‘No worries’, ‘It’s all good’

Stay laid back, we’re not going anywhere. The world has gotten fairly used to hearing nothing but reports of turmoil coming out of Brazil over the last few years, but this is not a country that values the headless-chicken approach to organisation. Stay calm, relax, it’ll do you the world of good.

3) Jeitinho, o jeitinho brasileiro

/zhey-tcheen-yoo/

Meaning: ‘The Brazilian way of doing things’, ‘where there’s a will, there’s a way’, ‘by hook or by crook’, ‘loophole’

This word holds a key insight into the way Brazil works when the going gets rough. A diminutive of the word jeito (‘way’), this refers to the ability to find a way around irritating obstacles – often referring to a law, a rule or some bureaucratic black hole.

This could involve: finding a friend at the front of the queue when in a rush, squeezing an extra person onto a fully-booked bus, using an upturned iron and hairdryer to cook food when no other heat source is available. These are all within the wide remit of o jeitinho brasileiro.Seriously.

The word can have mixed connotations of inventivity, shrewdness, and mild illegality.

The concept is for some a positive marker of national identity, and for others a damning trait, when it strays close to cheating – see one other definition of jeitinho – ‘a arte de ser mais igual que os outros’ (‘The art of being more equal than others’)

4) Para inglês ver

/pa-ruh eeng-layz ver/

Meaning: ‘For the English to see’, ‘for show’, ‘lip service’

There is no good direct translation for this one, but the phrase tells a fascinating story.

In short, it is said with a wry smile of laws or rules that are considered nonsensical, insincere, or impractical, and which are only there as a tip of the cap to some authority.

It emerged from a sordid tale of slavery, colonialism, and coffee-swilling Brits abroad.

Britain, having been the major player in the transatlantic slave trade for centuries, became the first country to abolish the practice of selling people (although not necessarily that of owning them) in 1807.

Following abolition at home, Britain began to target the traffic of other countries. In the wake of Brazil’s independence from Portugal in 1822, Britain pursued an anti-slavery agenda with the young country in exchange for international recognition of its independence. In 1827, the young nation pledged to end the import of slaves within three years.

In reality, though, the trafficking and forced labour of people was the economic cornerstone of the Brazilian economy, which relied not just on its plantations’ production of coffee, but also on the mercantile British to buy the stuff and sell it back on to Europe. This situation of economic dependence was unlikely to cease overnight.

During this three-year grace period, there was a frenzy as traders stockpiled slaves in fear of the impending restrictions, meaning there was in fact a massive spike in the number of people shipped to Brazil.

The ruling elites feared that an end to slavery would crush Brazil’s agricultural economy as well as their political influence, and so the chances of systemic change were doomed from the outset.

The law which finally declared that all Africans who were brought to Brazil would be free was therefore reduced to a kind of lip-service proclamation to keep the British surveyors happy, while in reality the Brazilian slave trade underwent a boom in the following years. A law ‘para ingles ver’ thus refers to something done for show to placate some authority while there is no intention of practically carrying it out.

An example from today’s usage would be a £50 million cable car installation in the Rio favela of Alemão which was considered a scandalously impractical waste of money.Courtesy of TimeOut Brasil

It was supposed to improve connectivity for the favela’s poor residents with the rest of the city, but was somehow designed with a maximum daily capacity of under half of the favela’s population. The capacity itself was also a moot point, because the cost of a cable car ticket priced out most of the favela’s residents, meaning that the eye-watering project became a tourist hub rather than anything of practical use – rather literally ‘for the English to see’ in this case.

5) a) Pois não. /poyzh nao/

Meaning: ‘Yes’, ‘of course’, ‘may I help you?’ ‘You’re welcome’

b) Pois sim. /poyzh seeng/

Meaning: ‘no’, ‘no way’

‘Não’ means ‘no’ and ‘sim’ means ‘yes’. How, then, can pois não possibly be an affirmative, while pois sim is used as a negative? Fica tranquilo, take a breath, and be prepared for even your most basic conversations to be somewhat topsy-turvy.

6) Que diabo… Quem projetou esta cidade? Não faz sentido!

Meaning: “Who the hell designed this city? It doesn’t make sense!”

Brazil joins a club with Canada, Australia and South Africa for being one of the world’s major countries where most foreigners do not know where the capital city lies. The seat of power has jumped around a fair bit over the years, but has never been the biggest city (São Paulo) and has not been Rio de Janeiro for over 50 years.

In 1960, the federal government moved abruptly from the latter to the city of Brasília, which was purpose built to create a seat of government in the interior of the country to tip the scales of the country’s economic and political clout away from the coastline, where most of the action happens in Brazil.

It was a legendary orchestration of town planning conducted by the world-famous famous Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, who was responsible for dreaming up some of the most iconic buildings in Brazil and beyond, full of bold geometric forms and free-flowing curve

Pretty jaw-dropping stuff. Except that Mr. Niemeyer was perhaps a tad overzealous with his experimental town planning of the capital – given that he designed Brasília in the shape of an aeroplane. Yep, you read that right.

The mid-20th century was an area punch-drunk on the giddy potential that air travel technology allowed, and Mr Niemeyer in turn was keener on his futuristic symbolism than on his desire for day-to-day pragmatism. On the other hand, it turned out to be quite apposite, because Brasília is so far away from anything else you do actually need a plane to get there.

This country’s capital has stunning architecture to brighten up the nightmarish urban sprawl as you are forced to drive from Wingtip A to Propeller C in search of your daily bread. Ok, so Wingtip C doesn’t actually exist, but Brasília’s impracticality as a city for people to actually live in is notorious. Que diabo… Quem projetou esta cidade? Nao faz sentido!

While the majority of the games are in Rio de Janeiro, some of the events will be spread across venues in other parts of the country, including in Brasília.

7) Saudade

/sao-da-djee/

Meaning: ‘longing’, ‘yearning’, ‘a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist’

Like a meal that changed your life and can never be re-experienced in the same way. Or the park where you spent summer days as a child, now irrevocably cemented over to make way for Crossrail. Or a sepia-tinged era when Great Britain were olympically excellent at sports other than rowing. ‘Saudade’ is a powerful feeling of having loved and lost that every human experiences – and Portuguese captures it with a brilliantly wistful word.

8) Cafuné

/ka-foo-neh/

Meaning: ‘The act of running your hand through a lover’s hair’

Portuguese is the second most widely spoken Romance language, and cafuné is a word of glorious concision that highlights the romance of the language. Three little syllables to describe the act of running your hands through the locks of your lover! How tender. It is possibly the word least likely to be borrowed into the dictionaries of a nation as awkward as the UK. Except, of course any of Portuguese’s supposed ‘romantic’ qualities are nothing to do with its status as a Romance language – this simply means that it is a descendant of Latin, so most of its vocabulary and syntax is ancestrally ‘Roman’. Words like Cafuné, however, showcase a variety that is linked to the adventurous history of the maritime Portuguese. Many such words are believed to come from the Bantu languages of Africa’s Western coast, while elements of the vocabulary also come from indigenous American peoples and Asian languages such as Hindi, Malay, Chinese and Japanese.

9) Peixe não puxe carroça

/pey-she nao pou-she ka-ho-suh/

Meaning: ‘Fish don’t pull wagons’

There is no happy translation for this strange Brazilian idiom. The point of this one is that hard manual work deserves hearty food, and fish is too dainty to do the job. For a country with 4654 miles of coastline, seafood is a surprisingly second class citizen in the meat-obsessed repertoire of Brazilian cuisine. So if you whack out this phrase at a restaurant, you’ll know what to expect. Stewed meat. Roasted meat. Giant quivering hunks of barbecued bloody meat.

And you’ll be thankful or it.

That’s an ideal end to a hard day of watching other people’s athletic exertions.

The Today Translations phrasebook now draws to a close – hold it tight as you wander round Rio, and they’ll tell you you’re a natural. Beleza for now.