Mention of the Chinese language tends to make westerners’ eyes glaze over. All those unfamiliar sounds, the daunting cadences of untold tones, and the elegantly impenetrable jungle of the writing system – enough already, we’ll stick to learning French. But as our eyes stay glazed, many tend to miss out on the crucial detail that a unitary ‘Chinese language’ is a fallacy. And being aware of the basics of Chinese language politics could bring real benefits to businesses here.

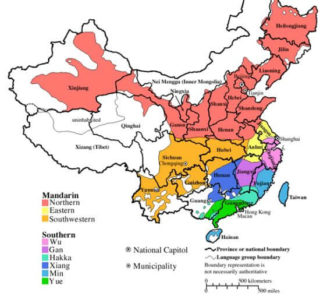

The Mandarin that we are accustomed to in our localisation projects is the Beijing dialect that has been legislated into prestige status as the national language. This prestige is very useful for preserving China’s unified national identity. But Ethnologue lists a full 297 living languages spoken in China. Given the sheer size of the country and its billowing population, even a regional language continuum can have millions more speakers than more recognisable languages in Europe. The Wu varieties have 80 million speakers, the Min have 70 million, and the Yue, which includes Cantonese, have over 60 million.

The promotion of one language may create a fractious dynamic with the others, whose speakers begin to fear their autonomy and ultimately their language’s very existence. It’s an old story – we’ve seen it in Canada with English & French, in Belgium with French and Flemish, and in Ireland with English and Gaelic, to name but a few.

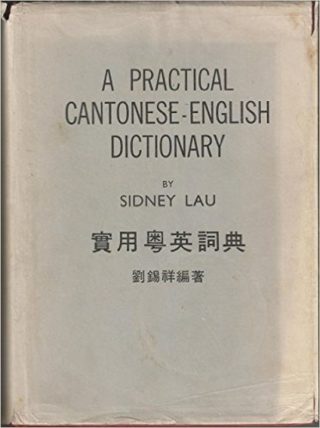

Language and identity are some of the most salient issues in Hong Kong today, and the ascent of Mandarin as a national language of government, education and business creates tensions that regularly threaten to boil over. Cantonese is in the top 20 world languages by speaker numbers – it is the dominant language in many if not most Chinese diaspora communities – yet its future vitality is not blessed with the most promising signs. In addition to Mandarin’s advance, there is a notable disconnect between Cantonese and other major world languages – for instance, the most recent English-Cantonese dictionary was published in 1977. Scarcity of up-to-date resources is never a promising sign for a language’s growth.

To deepen the challenge of understanding China’s language wars, we must touch on what we see. There is some confusion over the different Chinese scripts, but a script obviously is not the same thing as a language – English speakers share the Roman alphabet with languages as diverse as Lithuanian, Turkish and Vietnamese, yet we make no claims about their relatedness. Writing is secondary to speech, and these systems ebb and flow with the tides of politics. In China, the battle lies in the opposition between the densely intricate characters of the traditional script, used in Mandarin-speaking Taiwan, and Cantonese Hong Kong and Macau, versus the pared-down pragmatism of the simplified script, used pretty much everywhere else. The latter system was created and promulgated by the Communist government in the 1950s in an attempt to increase literacy rates and enforce the cohesion of a unified Chinese identity.

The arguments over the relative merits of traditional versus simplified still rage in academic circles, but on a practical level, the direction of the current tide is not in question. When we hear statistics about the prevalence of Chinese on the internet, they refer to Mandarin Chinese in simplified script. Cantonese-speakers may well feel left out – Google Translate has only in the last year or so decided to cater for the 60 million speakers of Cantonese. Although that said, the language is notoriously difficult to translate, especially without the massive banks of online language data that Mandarin enjoys. Other recent priority additions to the service include Frisian and Luxemburgish (combined speaker populations 1 million).

English is just an interested onlooker in Hong Kong’s language wars, but as ever, three’s a crowd. English is inevitably seen as an essential language for moving up the global ladder, and this is doubly predictable given Hong Kong’s recent colonial history. But in the last decade, Mandarin has become increasingly accepted as a language of administration, and instruction in elementary and secondary education. While the language laws of mainland China do not apply to Hong Kong and Macau, Mandarin has become the de facto language of educational instruction in a majority of schools – there is a consensus that 70% of schools in Hong Kong follow this trend.

What is at stake with this shift? While Cantonese is vibrant for the moment, with 97% of ethnically Chinese in Hong Kong reporting fluency in Cantonese, educational and cultural changes could point to a demographic tidal wave in the coming decades. Observers fear that in the medium term, the survival of this ancient language is threatened, as it is crowded out in the lives of younger speakers, whose parents report widespread struggles with fluent expression.

Moreover, there are worrying precedents; the Wu variety Shanghainese used to be spoken throughout the entire Yangtze region, but it has seen its speaker population fall to just 14 million. Language shift is underway in both these cases, and the end of that road is language death. Of course, reaching that point is by no means a foregone conclusion; the vitality of Cantonese is just weaker than it once was, but things could change. The hypothetical death of a language with as rich a cultural history as Cantonese would be devastating, and preservation is high on the agenda of many in this highly emotional subject.

It is enlightening to illustrate just how charged the issue is. In January 2014, the Chinese education Bureau released an article about the value of bi- and tri-lingualism in Hong Kong. It stated that “nearly 97% of the local population learn Cantonese (a Chinese dialect that is not an official language.)” The use of the word ‘dialect’ prompted seething public outrage. The question of what distinguishes a language and a dialect is a vain one, frequently asked and never truly resolved. Contrary to popular belief, the division rarely has any basis whatsoever in any qualitative linguistic grounds, but is a function of political fluxes. The distinction is arbitrary and changeable; in Max Weinreich’s lapidary summary, ‘a language is a dialect with an army and a navy’. Just look at the languages of former Yugoslavia, once just seen as part of a wider dialect continuum, and now known as Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian or Montenegrin – according where you stand relative to the border. Yet few would dare call those languages dialects now, despite their total mutual intelligibility.

By the same logic, Mandarin and Cantonese are not mutually intelligible, have different histories, vocabularies and totally separate tonal systems – so the public casting of Cantonese as a subsidiary offshoot of Mandarin was bound to stir up antipathy in Hong Kong.

Language wars are an analogue of the political rifts that exist between Hong Kong and Beijing – rifts which don’t look set for a peaceful healing anytime soon. For the government, the unity of the country is a priority. Official proclamations reflect this – but “One language, two ways of speaking” rings hollow in the ears of many Hong Kong residents.

Since Beijing made Mandarin the official language of the country in 1982, regional languages have been edged out of public life. The use of non-Mandarin Chinese is regulated by the State Administration of Radio, Film & Television, to the extent that broadcasting in ‘dialect’ requires permission from the government. In Guangzhou, the third largest Chinese city and a Cantonese-language hub, protests erupted in 2010 when the state tried to make the local TV station switch its primary broadcasting language to Mandarin. This demonstrations ultimately prompted the rejection of the scheme. The encroachment of simplified script is frequently in the news – in both senses. This generates enormous and visible resentment from Hong Kong locals.

In order to do business with China, the West needs to make more of an effort to understand China on its own terms. China is an extraordinarily complex country, and while our initial interest in localisation was right to appeal to Mandarin and Simplified script, there is wisdom in turning attention to localisation in Cantonese and Traditional script. Western businesses can exploit the present tension to their own advantage; and because localisation is about an appeal to the native feelings of your audience, it is less of an exploitation than an olive branch proffered. Hong Kong’s language wars will always raise the emotional hackles of Cantonese speakers, and a counter-movement is certainly underway. It is in trend with localisation becoming ever-more specific and, well, local. Pigeonholing a country of China’s diversity necessarily means you’ll never know what you’re missing out on.